|

| |

|

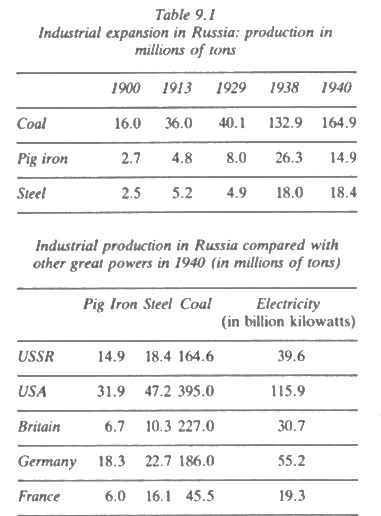

9.2 WHAT WERE THE ECONOMIC PROBLEMS, AND HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS STALIN IN SOLVING THEM? (a) The problems (i) Although Russian industry was recovering from the effects of the war, production from heavy industry was still surprisingly low; in 1929 for example, France, not a major industrial power, produced more coal and steel than Russia, while Germany, Britain and especially the USA were streets ahead. Stalin believed that a rapid expansion of heavy industry was essential so that Russia would be able to survive the attack which he was convinced would come sooner or later from the Western capitalist powers who hated communism. Industrialisation would have the added advantage of increasing support for the government, because it was the industrial workers who were the communists' greatest allies: the more industrial workers, the more secure the communist state would be. One serious obstacle to overcome, though, was lack of capital to finance expansion, since foreigners were unwilling to invest in a communist state. (ii) More food would have to be produced, both to feed the growing industrial population and to provide a surplus for export which would bring in foreign capital and profits for investment in industry. Yet the primitive agricultural system was incapable of providing such increases.

(b) The approach Although he had no economic experience whatsoever, Stalin seems to have had no hesitation in plunging the country into a series of dramatic changes designed to overcome the problems in the shortest possible time. In a speech in February 1931 he explained why: 'We are 50 or 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in 10 years. Either we do it, or we shall be crushed.' NEP had been permissible as a temporary measure, but must now be abandoned: both industry and agriculture must be taken under government control. (i) Industrial expansion was tackled by a series of Five Year Plans, the first two of which (1928-32 and 1933-7) were said to have been completed a year ahead of schedule. though in fact neither of them reached the full target. The first plan concentrated on heavy industry - coal, iron, steel, oil and machinery (including tractors), which were scheduled to triple output; the two later plans provided for some increases in consumer goods as well as in heavy industry. It has to be said that in spite of all sorts of mistakes the plans were a remarkable success: by 1940 the USSR had overtaken Britain in iron and steel production, though not yet in coal, and she was within reach of Germany:

Hundreds of factories were built, many of them in new towns east of the Ural Mountains where they would be safer from invasion. Well-known examples are the iron and steel works at Magnitogorsk, tractor works at Kharkov and Gorki, a hydro-electric dam at Dnepropetrovsk and the oil refineries in the Caucasus. How was it achieved? The cash was provided almost entirely by the Russians themselves, with no foreign investment; some came from grain exports, some from charging peasants heavily for use of government equipment and the ruthless ploughing back of all profits and surplus. Hundreds of foreign technicians were brought in and great emphasis placed on expanding education in technical colleges and universities and even in factory schools, to provide a whole new generation of skilled workers. In the factories the old capitalist methods of piecework and pay differentials between skilled and unskilled workers were used to encourage production; medals were given to workers who achieved record output; these were known as Stakhanovites after Alexei Stakhanov, a champion miner who in August 1935, supported by a well-organised team, managed to cut 102 tons of coal in a single shift (by ordinary methods even the highly efficient miners of the Ruhr in Germany were managing only 10 tons per shift). Ordinary workers were ruthlessly disciplined: there were severe punishments for had workmanship, accusations of being a 'saboteur' when targets were not met and often a spell in a forced labour camp. Primitive housing conditions and a severe shortage of consumer goods (because of the concentration on heavy industry) on top of all the regimentation must have made life grim for most workers. As Richard Freeborn points out: 'It is probably no exaggeration to claim that the First Five Year Plan represented a declaration of war by the state machine against the workers and peasants of the USSR who were subjected to a greater exploitation than any they had known under capitalism.' However, by the mid- 1930s things were improving as benefits such as education, medical care and holidays with pay became available.

|

|

|

| |